I’ve been investigating applications that use the Signal Protocol in order to determine if the Signal Protocol for asynchronous messaging might be appropriate for use for applying to SecureDrop messaging in the future. In this post are some notes from reading the Signal Protocol specifications, which I thought might be a useful reference and explanation for others. If you notice an error, or have other thoughts on anything here, feel free to drop me a note on Twitter or by email.

The protocol consists of two main parts, one for establishing key agreement between two parties, and another for “ratcheting” or deriving new ephemeral keys from that initial key material.

Key Agreement using Extended Triple Diffie-Hellman (X3DH)

This is the process that occurs on first-time messages.

The full description is covered in this specification. I use the same nomenclature as the specificiation for ease of comparison.

X3DH is used in order to set up a shared secret between two parties. In this scenario we have a a server which is where we’ll store information in case either party is offline. We also have our two users:

- Alice(👧🏼) who is online.

- Bob(👦🏽) who is offline. But Bob has helpfully published some data to the server for Alice to use to send him secure messages while he’s offline.

Alice👧🏼 and Bob👦🏽 will generate several elliptic curve key pairs using either Curve25519 or Curve448. How these curves can be used in Diffie-Hellman key exchange is described in RFC 7748, Section 6.

For Alice👧🏼, she has the following public keys:

- long-term identity public key $IK_A$

- emphemeral public key $EK_A$

Bob👦🏽, who recall is offline, has published the following public keys to the server:

- long-term identity public key $IK_B$

- signed public prekey $SPK_B$. Bob👦🏽 will publish new signed prekeys from time to time, which will replace the old one. He obviously publishes both the prekey and the corresponding signature (with his long term identity key). When Bob👦🏽 replaces a prekey, he’ll want to delete the private key of the old keypair after waiting a period of time to allow for recently sent messages to be delivered.

- $n$ one-time public prekeys $OPK^{1}_{B}$…$OPK_{B}^{n}$. Since these are one-time use, these will eventually run low (especially if Bob👦🏽 here is a popular fellow) so occasionally Bob will upload additional prekeys. When Bob receives a message using a public prekey, he’ll use the private key to process the message, and then delete the corresponding private key.

When Alice👧🏼 wants to send an initial message, she:

- Fetches Bob👦🏽’s long-term identity public key.

- Fetches Bob👦🏽’s signed public prekey and the signature. She verifies the signature (and stops if the verification fails).

- She fetches one of Bob👦🏽’s one-time public prekeys ($OPK^{1}_{B}$) - if one is available. Else she skips this step.

These items are found in a PreKeyBundle.

Next, four Diffie-Hellman (DH) shared secrets are derived using:

- Alice👧🏼’s long term identity key $IK_A$ and Bob👦🏽’s signed pre-key $SPK_B$.

- Alice👧🏼’s emphemeral key $EK_A$ and Bob👦🏽’s long term identity key $IK_B$.

- Alice👧🏼’s emphemeral key $EK_A$ and Bob👦🏽’s signed pre-key $SPK_B$.

- Alice👧🏼’s emphemeral key $EK_A$ and Bob👦🏽’s one-time public prekeys $OPK^{1}_{B}$.

Since the private key material for DH secrets 3-4 above will be deleted after use, these provide forward secrecy. This also means that in the future if an attacker collecting ciphertexts is able to compromise Alice👧🏼’s long-term identity key, the attacker cannot recover all four DH shared secrets since the ephmeral key material is long gone, thus they are unable to decrypt the ciphertexts encrypted using secrets derived from these DH secrets. By using the long-term identity keys - which can be verified using manual verification of safety numbers - in steps 1-2, these steps mutually authenticate Bob👦🏽 and Alice👧🏼.

Next, DH outputs 1-3 (and 4 if available) are concatenated and used as an input for HKDF, an HMAC-based Key Derivation Function (KDF). A KDF does what it sounds like: takes some input and produces cryptographically strong key material. HKDF is defined in RFC 5869. In our protocol, the output of HKDF is a shared key $SK$! These three (and sometimes four) DH key exchanges give the protocol its name.

At this point, Alice👧🏼 can now send a message to Bob👦🏽. She sends him $IK_A$, $EK_A$, the ID of the one-time prekey she used ($OPK_{B1}$) (Bob👦🏽 will delete the corresponding private key material once he processes the message), and the ciphertext of her message encrypted using the shared key $SK$, which Bob👦🏽 can also derive.

Implications

An attacker that is able to compromise the long-term identity key can masquerade as the user. They can sign prekeys and create new sessions. But, provided an attacker does not have access to previous ephemeral prekey (i.e. private) key material - which are deleted in the protocol after use - the attacker will not be able to reconstruct prior $SK$ and thus decrypt previous ciphertexts. If the private keys corresponding to currently uploaded prekeys, either one-time or signed, were compromised, they should be replaced.

The specification also states that rate limits should be in place for getting a one-time prekey: this prevents an attacker from exhausting one-time prekeys, which would force Alice👧🏼 to fall back to using only Bob👦🏽’s signed prekey.

Double Ratchet Algorithm

At this point once the initial shared secret is established, the “ratchet” comes into play.

The full description is covered in this specification in the Double Ratchet without header encryption section. I use the same nomenclature as the specificiation for ease of comparison.

KDF chain

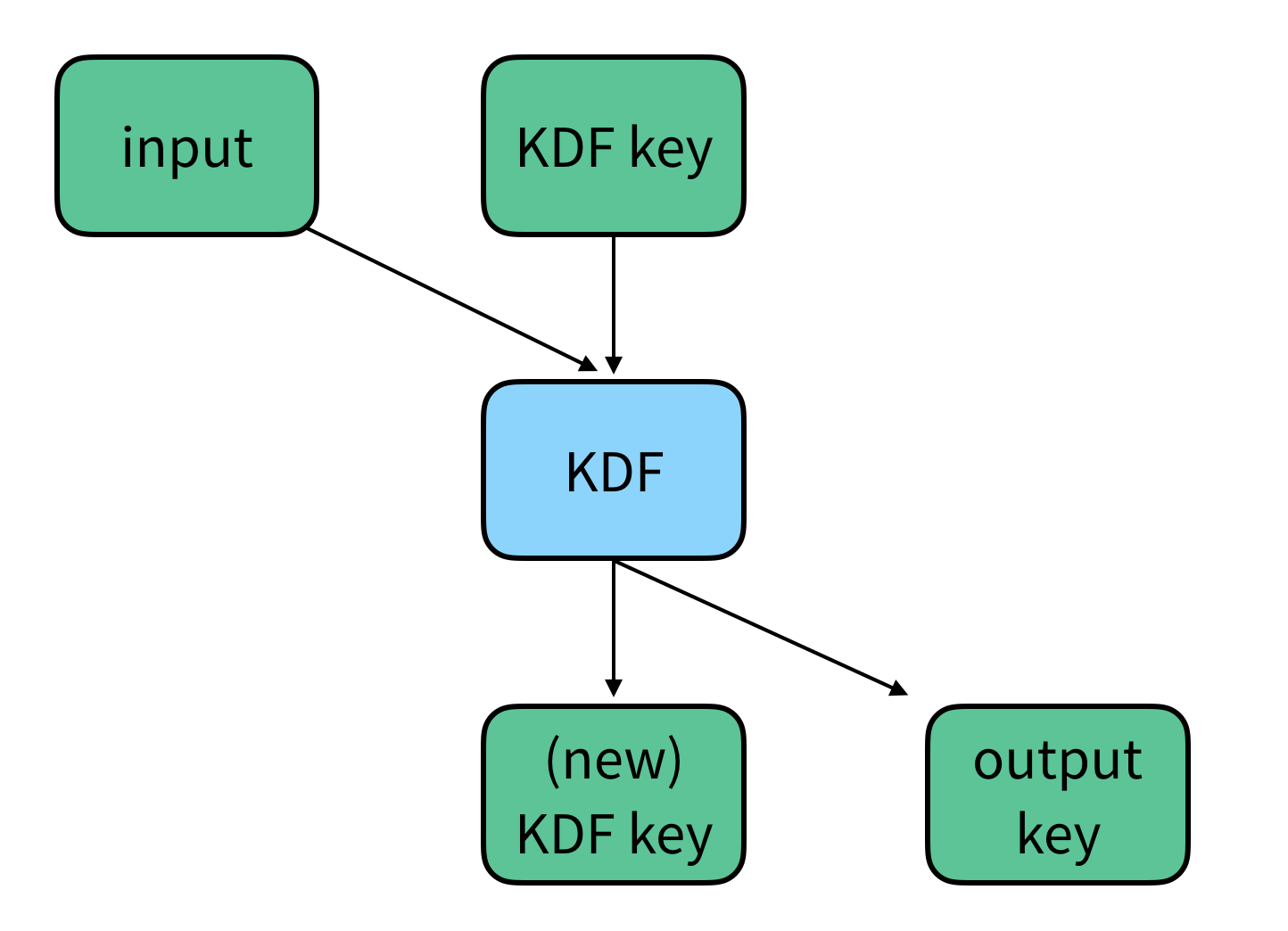

A KDF chain is when a key and some additional input is used as input to a KDF, producting key material, some of which is used as a new KDF key, and some of which is used as an output key. The output keys are used, and the next step in the KDF chain uses the new KDF key as an input. Each step of the KDF chain looks like the following:

Symmetric-key ratchet

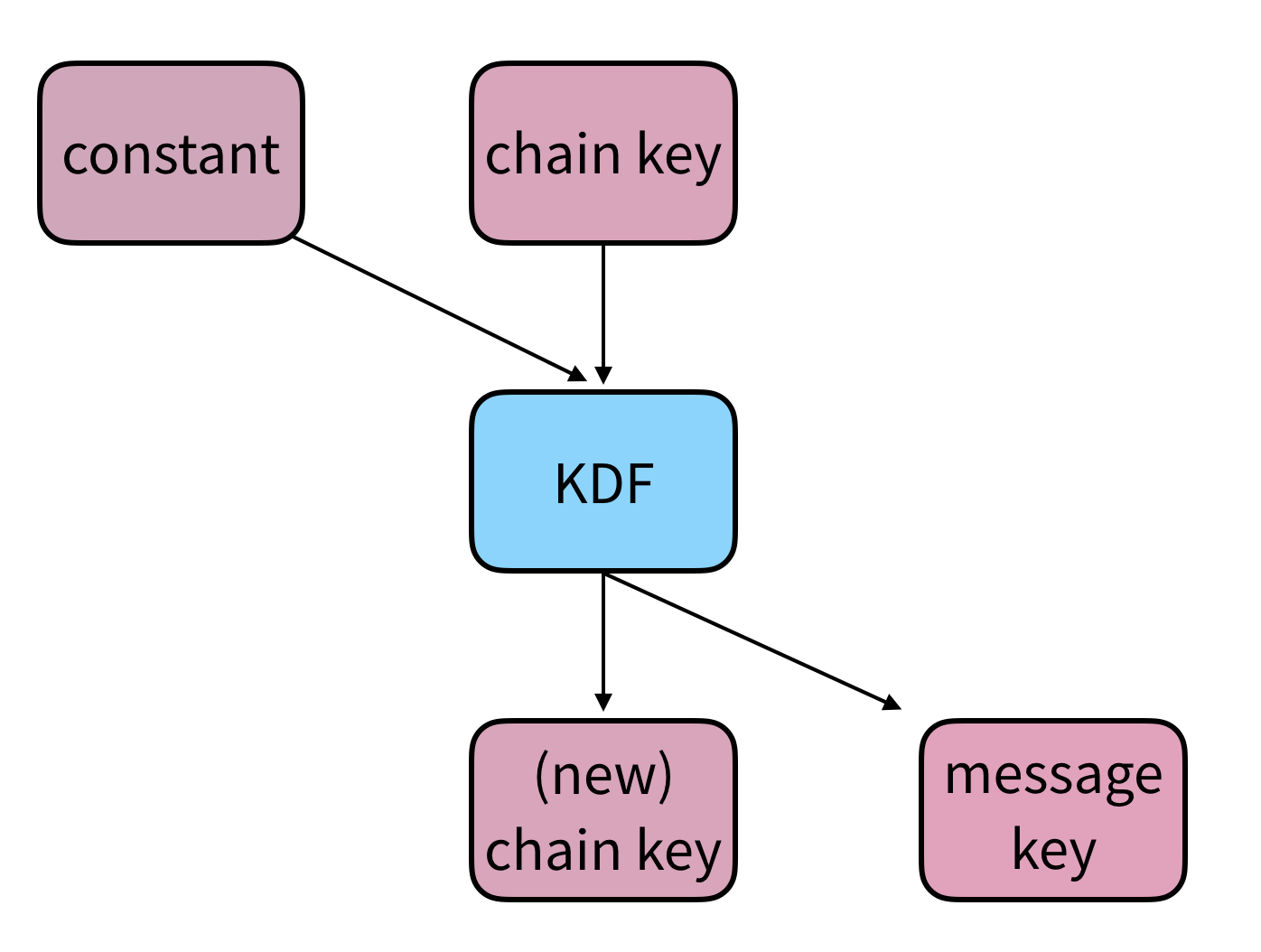

A “symmetric ratchet” is a KDF chain that is used to derive per-message keys. Signal’s “Chain key” refers to the KDF key for each of the symmetric-key chains.

A single step in the symmetric key ratchet looks like the following:

DH Ratchet

The DH ratchet is the process by which chain keys in the symmetric ratchet are updated.

Each party has a ratchet key pair, which is a public-private Diffie-Hellman key pair.

We observed in the X3DH protocol that in the first message Alice👧🏼 sent, she included the public part of her emphemeral key $EK_A$ such that bob could derive the same shared secret $SK$.

In subsequent messages, Alice👧🏼 (and Bob👦🏽) can advertise new public keys (new “ratchet” public keys), which when Bob👦🏽 (and Alice👧🏼) receives he can use to construct new DH ratchet shared secrets using the local corresponding ratchet private key. Alice👧🏼 and Bob👦🏽 take turns ratcheting the DH secrets forward. Senders must include the sender ratchet key in each Signal message.

Signal Protocol

Putting this together, Alice👧🏼 and Bob👦🏽 each have:

- a DH ratchet

- a root (symmetric-key) chain

- a sending (symmetric-key) chain

- a receiving (symmetric-key) chain

Alice👧🏼’s sending chain and Bob👦🏽’s receiving chain are the same, similarly Alice👧🏼’s receiving chain and Bob👦🏽’s sending chain also are the same. Output keys from the sending and receiving chains are used for individual message encryption and decryption.

Once a message key is used (i.e. for encryption or deletion), it is deleted by clients. If messages are delivered out of order, the receiver can just ratchet the chain forward to get the key material for the most recent delivered message, and store the message keys from the previous steps until they are delivered.

The root chain takes as input DH secrets from the DH ratchet (derived as described in the prior section). The output keys from the root chain are new chain keys for the sending and receiving chains. As stated above, the message keys from those sending and receiving chains are used to encrypt and decrypt individual messages.

The initial root key for the Double Ratchet protocol is the SK generated from the X3DH protocol. Initially $SPK_{B}$ becomes Bob👦🏽’s initial ratchet keypair.

Properties

In summary, in addition to protecting the confidentiality of messages, some other useful properties of the above protocol are:

- Deniability - anyone can claim a message came from one of the participants at the end of a conversation.

- Forward secrecy - If long-term keys are compromised, prior messages cannot be decrypted. The key material to decrypt them is ephemeral and will have been deleted.

- Self-healing and “future secrecy” - If a key is compromised, the protocol heals, meaning that future communications will return to a state unknown to the attacker. This is done by updating chain keys using the DH ratchet.

- Authentication - If key fingerprints are mutually verified, the protocol provides end-to-end authentication.