This is a writeup of a talk that I gave at Defcon 23’s Cryptography and Privacy Village back in August 2015. The presentation included a brief primer on machine learning as some in the audience were unfamiliar with the topic, so skip down to “Is there really a problem here?” if you are already familiar with ML. Thanks to all who attended and for the excellent questions and comments! References are embedded as links in the text.

Introduction

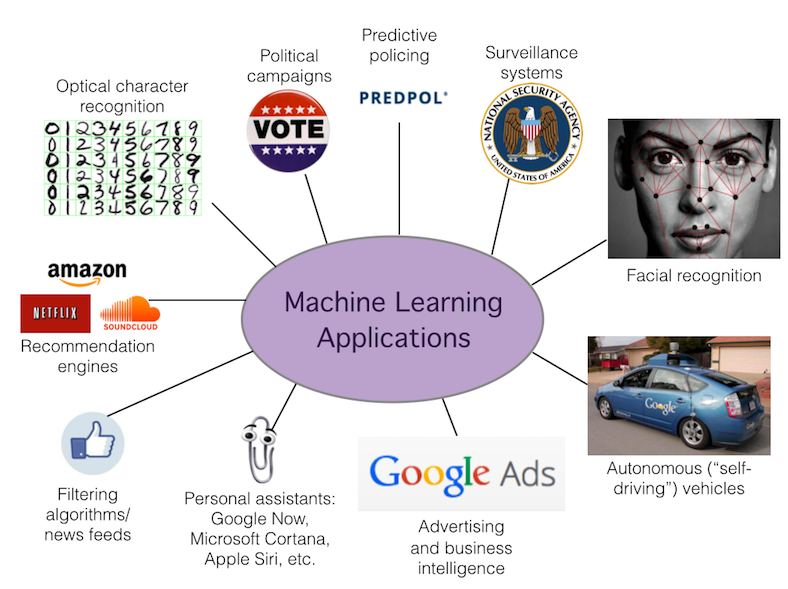

As a society we have an ever-increasing amount of information, data which only has value if we are able to extract meaningful insights - the needle in the haystack. In data science, we use machine learning algorithms and methods like A/B testing to do this. Data science enables us to learn about systems, determine how to optimally make decisions and infer new information not present in the data. These data analysis techniques are incredibly useful and are becoming more powerful due to more and better data as well as the due to the development of increasingly more intelligent systems. These methods have spread into a wide range of areas:

Let’s step through a few of the problems that machine learning can be used for:

- Advertising: This is probably the most familiar application. The main difference here is that we’re increasingly moving from very coarse-grained advertising systems to extremely finely targeted ads.

- Political campaigns: Machine learning is used to build predictive models about individual voters to determine which voters a campaign should target and build experiments that can be used to determine what the optimal action the campaign can take to bring about their desired goal.

- Surveillance: Machine learning can be used to classify people into suspicious or not, such as the system that puts people onto the no-fly list.

By machine learning here, we’re referring to a set of computer programming techniques that adaptively learn from data: they learn programs from data instead of requiring a set of rules to be explicitly written down by a programmer.

For example, if I want to write a program that recognizes handwritten characters, I can write down a list of rules, telling the computer specifically what shapes to expect in a given character. I would need to ensure that the program also can handle different handwriting styles as well as both printed and cursive text. Even for a single character this process could get quite laborious considering the wide variation in handwriting. Instead, one could use supervised machine learning, where a computer learns the rules that best identify a character using many examples of handwritten letters.

Supervised learning methods are what we will be focusing on in this discussion. First, we’ll look at a cartoon example to set up some nomenclature and build some intuition about how this is done.

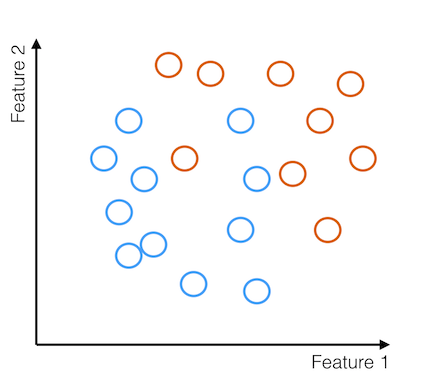

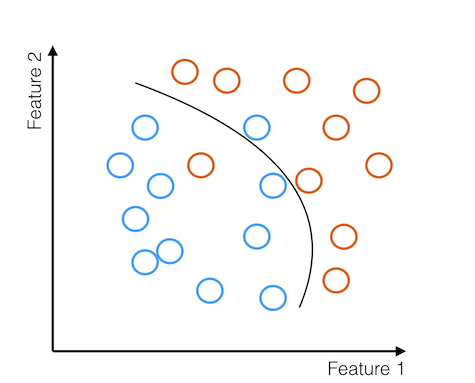

Let’s take a canonical classification problem: I want to classify some images into cats, which I will denote with orange circles, and dogs, denoted by blue circles. In order to use supervised learning to approach this problem, I must get examples of past images and whether they were classified as a cat or a dog - this is my training set. I then take both my training and testing data and construct features, quantities in the data that might be predictive of the target - whether a given image is a cat or a dog. These features could be quantities as simple as the intensity in a given pixel or the mean color in an image. Here’s a cartoon view of these training examples distributed in feature space:

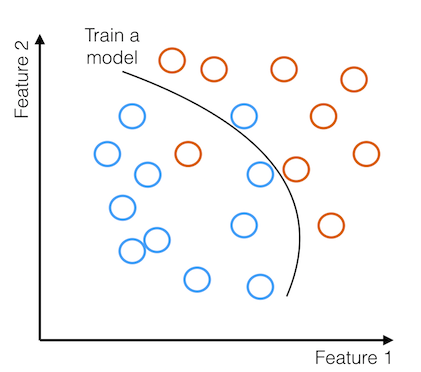

Then we take these examples and their derived features along with a learner - a machine learning algorithm - which will dynamically determine which features are predictive of the label and by how much.

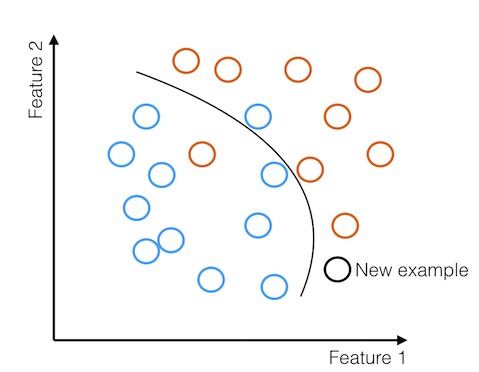

Then, this trained model can be used with a new example from our testing data to predict for the new example whether or not the image contains a cat or a dog, based on what side of the decision boundary the example falls on.

This is a very brief and high level overview of the nomenclature that we’ll be using in the remainder of the discussion.

Is there really a problem here?

From the applications I describe above, it’s clear that many of these machine learning systems can and will have profound positive impacts on human society. For example, autonomous vehicles have a huge potential for reducing human injury and death due to car accidents, one of the most common causes of death in the United States. Predictive systems can be used to make better use of taxpayer dollars, as well as can help find and correct problems like the use of lead paint in homes before serious damage or injury occurs.

But these systems are also used for applications that are not as noble, as in the case of mass surveillance. And there might be unintended consequences of relying on systems like these, which the public and sometimes even the designers may not fully understand. We need to make sure that we are thinking about the ramifications of our reliance on machine learning methods with respect to the principles that the privacy advocacy community cares about. In the privacy advocacy community we discuss surveillance a great deal for good reason. So to broaden the scope of the discussion, in this talk I’m going to focus on potential problems due to algorithms beyond surveillance and discuss other issues related to implementation and power. It would be great to have more discussion in both the privacy advocacy and data science communities about this topic.

In terms of problems that can arise, I’ll discuss implementation issues related to biased input data as well as usage issues, when systems are deployed that can be easily misused due to little or no oversight.

Input Datasets

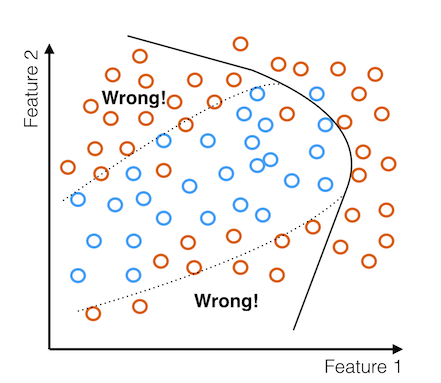

As explained in the introduction, these are systems that learn by example. The examples must be representative of the truth. If the input data are not collected in an unbiased way, then the model will be biased in some way. In an ideal world, training datasets would be colleced by random sampling, where the probability of collecting an example is uniform, however, most sampling out there in the real world is not random. Strong selection effects are present in most training data, and in order to generate an accurate model, these need to be understood. Problems arise when input data is treated as unbiased and is used as input to an algorithm which is then treated as impartial and unbiased. Let’s go back to our cartoon view of examples in feature space to see why this occurs:

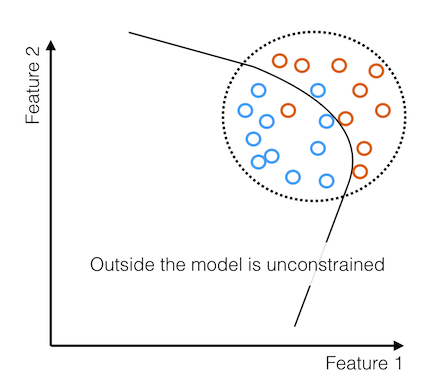

Here we have our examples in feature space, with a decision boundary drawn through the examples. But let’s zoom out:

We see that the decision boundary extends into regions of feature space that our examples here are not providing much information about. Outside this dotted region, the model is basically unconstrained.

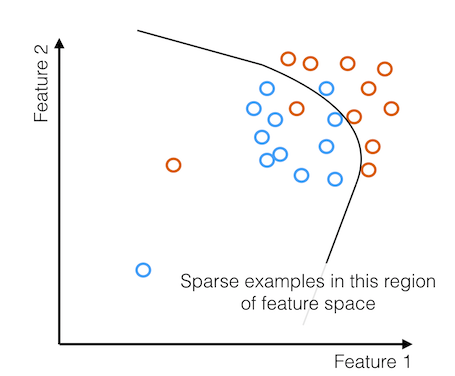

Even with a few examples, the coverage is so sparse that a few examples don’t help the model much.

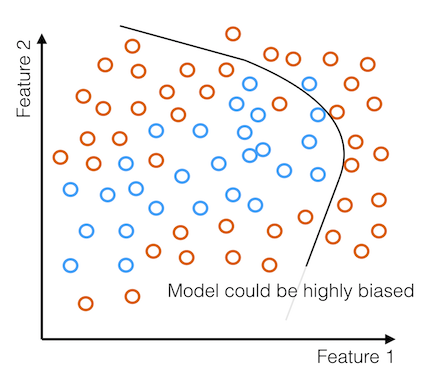

When the input data is biased in this way, we end up with a highly biased model.

The model incorrectly classifies many examples. This is one major issue that is often handled poorly. Let’s look at a real world example to see how this might manifest itself in algorithms that are currently in use.

Predictive Policing

Police departments state that they are starting to direct more energy to crime prevention, which is one way that machine learning is used by police departments. The idea is to allocate resources more effectively and enable proactive and preventative policing strategies. Perhaps by allocating police officers to areas where crimes are likely to occur then you can prevent those crimes from even occurring: the mere presence of police will dissuade people from criminal acts. In the same vein, police officers could also surveil those individuals who are considered most likely to commit crimes. Here’s how the New York City police commissioner regards predictive policing:

These two types of crime prediction systems are:

- Individual: Crime probabilities for individual people. Used by the Chicago Police Department, which maintains a “Heat List” of people who are considered most likely to commit some violent crime. This is done using network analysis going two hops out.

- Spatially: An approach that is considered more tasteful (in terms of not evoking Minority Report as much) is to predict which areas are likely to have crimes committed in them within some time period. One issue immediately is that since humans tend to cluster and the same individuals tend to aggregate in the same areas, these two approaches are not totally dissimilar.

One of the major players in this space is a company called PredPol. They have a product that predicts crime probabilities on a spatial basis. On their website they say the following:

Their system does not use individual data: they use only type, place and time of crime. However, statements like this in isolation should in no way reassure people of the unbiased nature of predictive crime systems like these. There are inhereant biases in input data due to selection effects in input data. Selection effects include biases due to people not being equally likely to call the police. In addition, we know that for many crimes, such as marijuana-related offenses, white and black people infract at a similar rate, black people are far more likely to be charged with marijuana-related crimes due to biases in law enforcement.

If I were to naively feed this crime data into the model, I’ve unevenly sampled feature space, and could very well be oversampled in areas of low socioeconomic status. The model will then not be representative of the truth and policing strategies based on a model will send cops to these poor areas, thus systematizing the discrimination. The real danger here with systems like this is that they could easily become a self-fulfilling prophesy if improperly validated.

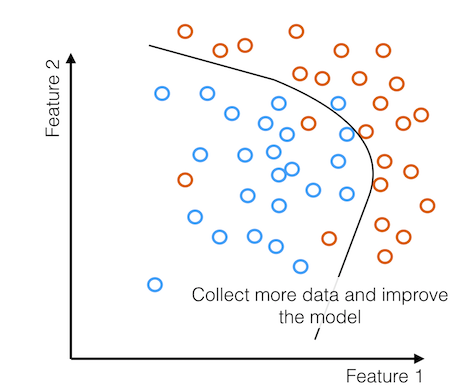

This can be done in a more responsible way. One way to proceed in a scenario like this is to allocate some fraction of your resources to targeting regions of feature space that are poorly constrained by the model. To make this system more fair, you don’t just need more data but the right data.

There are lots of other ways of dealing with biased training data such as reweighting the training data in feature space. There’s also a body of work in the machine learning literature on fair representations that aim to address some of the issues related to discrimination.

However, naive use of training sets is just one issue. Spatial aggregation doesn’t wash all these problems away, especially when the aggregation is done over very small areas. Predpol for example aggregates over 500 ft x 500 ft blocks, so this could be only a few houses. In this way aggregated data can still provide identifying information about individuals. Clearly, removing controversial features like race, criminal history, or even generally individual-level information does not magically erase all discriminatory issues with the training data.

I’m certainly not necessarily condemning all predictive systems here. But these are the sorts of questions we need to be asking manufacturers of these systems to ensure that they have thought carefully about these issues. Currently, there is no formal system to regulate or address these types of discrimination and bias concerns when it comes to machine learning implementation.

Filtering

Even if one is able to construct a system that is perfectly accurate, another concern is how these methods are used. One possibility that has been raised is the potential for manipulation of algorithms by the organizations that control them, their employees, or by attackers. These manipulations would be difficult to detect due to a current lack of transparancy and accountability.

A set of algorithms that are natural targets for manipulation are filtering algorithms. Filtering algorithms are necessary due to the firehose of data we are all currently trying to make sense of in our daily lives. We can sort through this data in a variety of ways:

- Reverse chronological order: Look at the newest items first

- Collaborative filtering: People vote on what they think is important

- Algorithmic filtering: Algorithms decide what should be shown or ranked highly

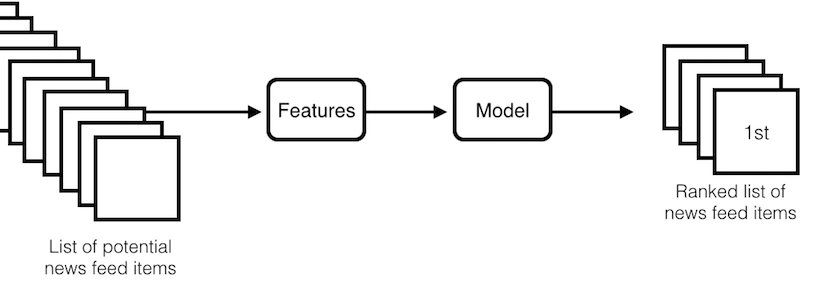

One such algorithm for algorithmic filtering is the Facebook news feed. This system takes a list of potential news feed items, builds features from them, puts them into a modeling system, and then produces an output of some ranked list of news feed items.

We have some idea of the features that are important for this system:

- Is a trending topic mentioned?

- Is this an important life event? Marriage, congratulations, etc.

- How old is the news item?

- How many likes or comments does this item have? How many likes or comments by people that I know?

- Is offensive (as judged by Facebook) content present?

The operation of this algorithm is important to understand as it determines what updates and news stories a Facebook user gets to see. In a scenario where the platform has over a billion users and a huge and increasing segment of the population relies on Facebook to get their news, we will see that even a small change can have a huge impact.

Manipulation

One high impact study discussed in the media regarding the manipulation of the Facebook news feed algorithm was Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. In this work, Facebook took almost 700k users and segmented them into control groups and positive and negative groups. The positive group was shown more items in their news feed that consisted of positive words. The negative group was shown more items in their news feed that consisted of negative words. Then Facebook observes the news items that are posted in response. And they find that in the positive group, more positive news items are posted, and in the negative group, more negative news items are posted. This is a statistically significant effect, because very tiny differences in the statistical properties of news feed items shown to users can have huge impacts.

Since you might be wondering, this type of work is legal if you accepted Facebook’s Data Use Policy. Agreeing to this document constitutes informed consent for this type of experimentation. Facebook is able to use this type of mechanism to shift people’s emotional states. However, there was another study that demonstrated using a similar mechanism, specifically by showing people a message about it being election day and showing them that some of their friends had voted, Facebook can statistically significantly increase the number of people that are likely to go out and vote. This is a lever that can be used to condition entire populations to act in a certain desired direction without them being aware. That’s a very scary idea and is the ultimate in mass social engineering.

In addition to corporations, their employees, and anyone that may infiltrate these organizations, governments are a natural entity to be interested in such powerful mechanisms of control. I encourage you to take a look at documents like this one from the UK’s GCHQ examining how to use psychological techniques to condition individuals towards obedience and conformity.

The issues associated with the usage of these algorithms is their opaque operation on proprietary data. These systems can enable manipulation. For all the issues described with algorithms, we need more information. The lack of information about their operation is the fundamental issue here.

The real problem is that we have no idea how many of these issues we are detecting. Many of the controversies that have occurred in recent years related to algorithms have been due to papers or admissions by the companies themselves. Both of the studies on manipulating the Facebook news feed were published by Facebook researchers. We need to make sure that we are building tools and advocating for policies that will enable the early detection of manipulation and discrimination and ensure that there is a mechanism for redress.

Time for action

The first step is stronger consumer protections. People should know how their data is being used and to that end we need more explicit data use and privacy policies. Users need this so they can make an informed decision. Facebook and other companies should more clearly and explicitly state how they use their users’ data, especially with respect to experimentation. There should also be a capacity for users to opt-out (or even better: opt-into) experimentation. There are bodies like the Federal Trade Commission in the US that can investigate and pursue companies that do not follow their own policies.

Next, all these systems leverage data. The situation is that the party who has access to the data as well as has the skills and resources to leverage the data has the power. Obviously reducing the amount of data collected helps - something that can be done by building systems that are private by design. For example, there’s a lot of work that has been done in the academic community on schemes for privacy-preserving targeting advertising.

Another front to push forward on is advocating independent audits, open algorithms, and transparency. A nice feature from some recommendation systems like amazon is the ability to enable you to determine why a given result was ranked highly, e.g. showing what other items have you purchased. Providing rankings of feature importances is also incredibly useful for transparency reports. Of course, companies have no reason to do these things unless consumers or regulation demands it.

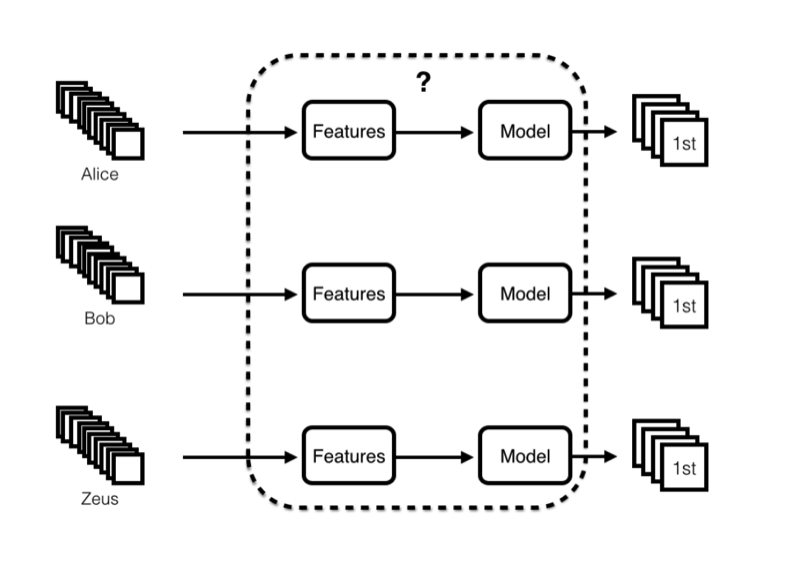

In terms of technology, one approach is to examine the algorithms themselves with black box analysis: correlating inputs and outputs to study the system in the black box. There is a schematic view of the facebook news feed algorithm. One can generate inputs using test accounts or real accounts. The outputs can be compared and differences in outputs across users can be examined.

One great recent example of how this analysis can be used to increase transparency is Xray. This is a really nice project done in the context of determining how ad placement is performed. The idea is to use test accounts, provide some interesting keywords as input and then see what ads get served in response. This can demonstrate that sensitive topics can be targeted and can also demonstrate data abuse. The group found some nice results when they applied this tool to Gmail: for example, when keywords associated with being in debt were present, they were served ads for new cars. If Google wasn’t reading your email then this wouldn’t be possible. But since they are reading your email, you can apply this type of analysis and find out how they are using your data. Similar techniques could be applied to other platforms. This is an excellent way forward that does not necessarily require the consent of the platforms involved.

Moving Forward

To practitioners: We need to be careful that we are using these systems in an equitable and responsible manner. Given biased input data, algorithms are not impartial and should not be treated as such. If we are to design systems that treat people fairly, then we need to be sure we carefully construct these systems not to discriminate.

And for us advocates, we need to recognize that these methods are extremely powerful and we have to demand more information and more accountability in order to monitor how they are designed and being used. We should push forward with both policy and technology to achieve this. The privacy advocacy community has a big role to play to show people what is being done here, because by and large we don’t know. And we’re not going to know unless we find out.